Meet EPA IT Specialist Linda Harwell

Linda Harwell’s love for the ocean started at a very early age. As a Navy brat, Linda moved around a lot, but she never lived far from a coast. Even now, working as a Social Scientist at EPA’s research laboratory in Gulf Breeze, Linda gets to see the ocean right outside her office every day.

Tell me about your background

Greetings from Florida! Meet EPA IT Specialist Linda Harwell.

My career with EPA started in 1993 as a contractor, and I became a federal employee in 1998. I was originally hired to assist with managing data for EPA’s Environmental Monitoring and Assessment Program, so I was doing “scientific data management” before it was cool. One of the things I really love about working at EPA is that I’ve always worked in a team environment. It has allowed me to be engaged in the whole research process. Now, I don’t just do data management—I do data analysis, publications and public engagement. It’s great because I thrive on diversity in my work. Today, I work in a coordinated effort assisting EPA's Office of Water with implementing the National Coastal Condition Assessment, which is part of the National Aquatic Resource Surveys Program. I also work in three different areas under EPA’s Sustainable and Healthy Communities Research Program: The Human Wellbeing Index, Climate Resilience Screening index, and Ecological Suitability Index. I guess you could say that my expertise is in data wrangling, indicator development, and more recently, developing my skills in the art of data science.

When did you first know you wanted to be a scientist?

It was the early 70s. I was enthralled with the TV series, The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau. I think everybody wanted to be a marine biologist after that show. It was just such a new and cool thing to most of us back then. It inspired me to become a certified scuba diver when I was 13 so I could experience the ocean for myself. While I am no marine biologist, the work that I do today helps to identify the relationships between the health of our natural environment and the social and economic benefits that influence people’s quality of life. I focus on coastal resources and communities whenever possible. I’ll never give up my love of the sea.

How does your science matter?

The science that I work in matters because we help distill some of the research EPA does into “bite size” pieces that both technical and non-technical audiences can understand. I work with colleagues to investigate, develop and test approaches to produce indicators that help us translate ORD research into information that people can relate to and immediately use. By extension, the public can see how EPA is working to address environmental issues that may be impacting the well-being of their communities.

What do you like most about your research?

There are a couple of things that tie for what I like most about my research. First is research storytelling. Helping people understand the research journey, from conception to outcome, is my favorite part of the research lifecycle. Equally important is working holistically when conducting research -- using skills I’ve learned from those who have taught and guided me throughout my career. My journey from scientific data management support to delivering research products has given me a well-rounded perspective that allows me to think “outside-the-box” to help find solutions to address research challenges.

If you could have dinner with any scientist, past or present, who would it be and what would you ask them?

When I look at my computer, I see a box with a bunch of wires and electricity running through it. I know it helps me do my job faster and better, but that’s all I really see. I’d like to dine and chat with Alan Turing, a person who looked at a similar, albeit much larger, box and conceptualized a machine that could “think” at a time when the term “computer” was largely thought of as a person who does calculations. In many circles, the Enigma deciphering algorithms were sort of the early whispers of artificial intelligence. And Turing conceptualized it given only a box of wires and electricity! What did he see that others did not? How did he imagine it? If he was alive today, would he be excited or disappointed by how things have evolved?

If you weren’t a scientist, what would you be doing?

I’d work for the Humane Society or something similar. I’ve always had pets growing up and know just how powerful the relationship between people and pets can be. In general, I have a really big soft spot for animals, especially those who need a safe place to call home whether home is a house or natural habitat.

If you could have one superpower, what would it be?

I’d like to be empathic, like the skill portrayed in Star Trek: The Next Generation (yes, I’m a Trekkie fan from way back). To be able to change the tone, timbre, or intensity of my conversation to match the mood and feelings of those around me would be really awesome. I could help minimize misunderstandings. I could do a better job at engaging others who feel they are not being heard. Or maybe just know when I need to be quiet.

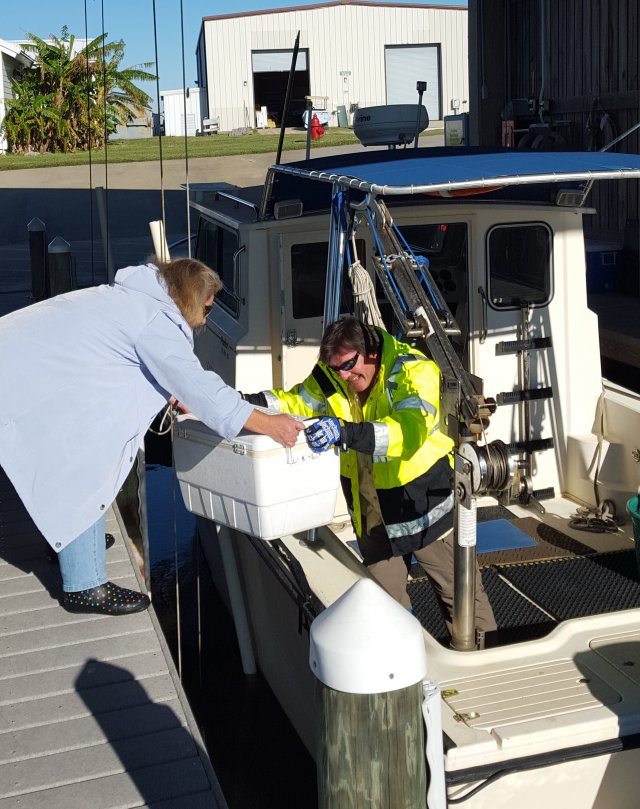

Harwell helps EPA's George Craven carry research equipment off of a boat.

Do you have any advice for students considering a career in science?

I always wanted to be a marine biologist, but I went with computers because it seemed to be a more practical thing to build a career on. Over time, it became clear that my affinity for the ocean was much stronger than my need to be practical. So, I shifted my skills from financial data management and analysis to science. Now I work as closely to aquatic research as I can. My advice to those considering a science career is find what interests you and pursue it, no matter how impractical people tell you that may be. Hang on to it. You may have to make many detours along the way, but if you hang in there the path will eventually lead you to where you want to be.

What do you think our biggest scientific challenge is in the next 20/50/100 years?

I think one of our biggest scientific challenges is being able to properly and thoroughly educate the public about what our research is telling them. Particularly when it comes to issues like climate change, environmental conservation, and environmental protection. What does all that mean to them? For a lot of folks, I think they see it as something intangible rather than something that may have an influence on their lives or their children’s lives. I’m a firm believer that environmental change will happen as a result of grassroots efforts. One person changing their views and interactions with nature may not have a big impact. But if the one person’s action inspires the next person to do the same, and then the next person follows and so on – well you get the picture. I believe that getting people to understand their dependence on nature will be crucial if we hope to avert global environmental disaster.

Whose work in your scientific field are you most impressed by?

My background is really broad and there are so many brilliant minds out there, so it’s hard to choose just one. Considering my current work in data science and communicating research results, I can think of a group of scientists at the CERN Laboratory. These researchers reportedly observed the Higgs boson particle, something considered a scientific unicorn. The discovery itself didn’t catch my eye, but one of the ways they chose to communicate their findings did. They created a particularly engaging communication piece that used live-action hand-drawings to describe the discovery, how the discovery was made, and why we should actually care about it. When was the last time anyone did that for something related to physics? Did the communication piece make me consider quantum physics as a new career path? Of course not, but it did give me pause long enough to learn a little more about the Higgs boson particle. I think that is the true power of science -- in the stories it can tell, and the discovery journeys it can inspire.

If you were stranded on a desert island with a group of other survivors, what would be your job?

I would be Team Mom! In team sports, the Team Mom is the one who does all the important stuff that no one remembers or cares to do. Snacks anyone?!

Editor's Note: The opinions expressed herein are those of the researcher alone. EPA does not endorse the opinions or positions expressed.