Climate Change Impacts on Energy

Overview

The U.S. energy system consists of all the infrastructure needed to collect, produce, distribute, store, and consume power for our homes, for our businesses, and while we are on the go. From manufacturing to agriculture, and health care to transportation, the nation depends on a stable energy supply.

Our energy system is vulnerable to a wide range of climate change impacts. These include rising temperatures and heat waves, cold and snow events, severe drought, intense rainfall, sea level rise, hurricanes, and wildfires. While these impacts differ from one region to another, they will continue to affect all areas of the country.1 Moreover, impacts to one part of the energy system or in one region can affect other parts of the system or other areas.

-

Wildfires. Warmer, drier conditions caused by climate change are expected to make wildfires more frequent and intense. When a tree came in contact with electrical distribution lines, it sparked the largest wildfire in California’s history, the 2021 Dixie Fire.41

-

Damage to Alaska infrastructure. Sea level rise, melting sea ice, and thawing permafrost are all expected to damage oil and gas infrastructure in Alaska, affecting energy production.42

-

Nuclear energy impacts. Nuclear power accounts for about one-fifth of U.S. electricity production.43 Many nuclear reactors use water from freshwater bodies or oceans to cool down.44 Rising water and air temperatures have already forced some nuclear plants to temporarily close to lower the risk of overheating.45

-

Reductions in hydropower. Drought, reduced mountain snowpack, and shifting snowmelt timing could affect hydropower energy production in the West, especially in summer, when demand is greatest.46

-

Hurricanes and extreme weather threats. Storm surge from hurricanes already threaten dozens of power plants and refineries on the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts.47 Rising sea levels will expose even more facilities to risk during extreme weather events.48

In addition, energy interacts with and depends on other sectors of the economy, such as water resources and transportation. Therefore, climate impacts on these sectors can affect the energy system.

Businesses, governments, and others are taking many actions to increase the resiliency of the energy system to climate change. For example, many states are upgrading and protecting their energy infrastructure from extreme weather.2 Governments and businesses are sharing information with each other through private/public partnerships. Companies and researchers are developing and installing innovative and renewable technologies (such as wind and solar) that help reduce air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. These actions not only help address vulnerabilities to the energy system, but also reduce the emissions that are making climate change worse.

Learn more about climate impacts on the energy sector:

- Top Climate Impacts on Energy

- Energy and the Economy

- Population Impacts

- What We Can Do

- Related Resources

Top Climate Impacts on Energy

Climate change may affect the energy sector at both local and regional scales. Four key impacts are described in this section.

1. Disruptions to Energy Supply

Extreme weather and natural disasters pose significant risks to the U.S. energy supply in all regions of the country.3 Energy systems on both the Gulf and East Coasts face more risk of damage from flooding due to hurricanes and sea level rise.4 More frequent and intense precipitation events are expected to increase the risk of flooding on infrastructure in the Northeast and the Midwest.5 In Arctic regions like Alaska, thawing permafrost causes land to sink and compromise fuel pipelines and other energy infrastructure.6

Overall, the climate is warming, and the atmosphere’s increasing capacity to hold moisture can lead to longer periods without rainfall. The warmth and variability in precipitation can lead to declining snowpack, shifts in snowmelt, and extended droughts—all of which affect water supplies needed for energy systems. For example, most U.S. power plants depend on rivers or lakes for cooling.7 Petroleum, natural gas, and biofuels production and refining also require a steady supply of water.8 Water shortages have already affected hydropower production, especially in the West.9 Without enough water, affected systems need to find new water sources or scale back their operations.

2. Interruptions to Electricity Transmission

Climate change threatens the ways in which power reaches our homes and businesses.10 For example, transmission lines are prone to damage during extreme weather. Snow and ice, wildfires, and extreme wind can damage above-ground powerlines and transmission towers.11 Flooding can affect underground powerlines and damage roads, railroads, pipelines, and storage facilities.12 Near the coast, storm surge can destroy petroleum storage tanks and wash out roads and railways.13

Warmer temperatures, especially hot summer temperatures, can affect power transmission. When temperatures rise, the carrying capacity of transmission lines decreases.14 Summer months also present more wildfire risks, especially in the Southwest.15 Wildfires can disrupt energy networks significantly when they affect transmission towers and powerlines.16,17 In some areas, faulty or fallen powerlines (or lines that come in contact with trees) can start wildfires. This risk is why some utilities shut down powerlines when high winds are forecast.18

3. Strain on the Energy System

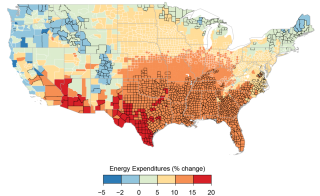

Temperatures are rising in all regions of the United States.19 As the climate warms, Americans are expected to use more energy, mostly electricity, for cooling.20 This higher demand will also increase the chance of blackouts or other power disruptions.21

A warming climate also means that Americans are expected to use less energy for heating their homes in the winter.22 However, increased summer demands for cooling are expected to outweigh any energy-use reductions from lower heating needs.23

4. Increased Air Pollution and Climate Change

As the demand for cooling increases across the nation, more electricity must be produced to meet this demand. Increasing energy production is likely to increase emissions of certain air pollutants and greenhouse gases that contribute to climate change.24,25

For more specific examples of climate change impacts in your region, please see the National Climate Assessment.

Energy and the Economy

An affordable and reliable energy supply is critical to the country’s economy.26 In 2023, the U.S. produced about 102.82 quadrillion British thermal units (Btu) of energy, about a 4.4% increase from 2022, and imported about 21.70 quadrillion Btu.27 Energy produced in the United States, but not consumed here, is exported to other countries. Fossil fuels (petroleum, coal, and natural gas) accounted for nearly 80% of U.S. energy production—both electricity generation and energy consumed directly—in 2020. The primary consumer sectors of energy in the United States are the industrial, transportation, commercial, and residential sectors.

The energy system is an important source of employment for Americans, providing jobs for about 8.3 million people.28 These jobs support power generation and transmission, fuel extraction and processing, and renewable energy and energy-efficiency installations and sales.

U.S. energy exports also contribute to the economy. Since 2019, U.S. energy exports exceeded total energy imports, as the United States was a net exporter of petroleum products such as crude oil, natural gas, and coal.29

Major disturbances to the energy supply, such as power outages or fuel shortages, harm the economy.30 For example, energy disruptions from extreme weather damage to energy infrastructure have cost billions of dollars.31 The nation’s energy system is also aging, with many components not designed to withstand the extreme weather conditions projected for this century.32

Population Impacts

Some communities have been historically overburdened by pollution. Low-income people, people of color, and linguistically isolated communities are more likely than the national average to live near power plants that burn fossil fuels.34 This means they can be exposed to air pollutants that cause or contribute to health issues, such as respiratory and heart diseases.35 As the climate changes and energy demand grows, communities may face increased levels of these emissions and associated risks.

Lower-income communities also carry a higher energy burden (the percentage of household income spent on energy costs) than those with higher incomes. On average, rural low-income households spend around 9% of their income on energy expenses.36 In comparison, rural middle and high-income households spend an estimated 3% of their income on energy.37 Many factors can contribute to higher energy burden including lack of insulation in housing, delayed maintenance of heating and cooling systems, and inefficient appliances.38 This energy burden may increase as the climate changes and energy demand goes up.

In addition, low-income communities often face barriers to accessing clean technologies that make energy more affordable. For instance, as of 2018, less than half of community-scale solar projects included households with lower incomes.40

What We Can Do

We can reduce climate change’s impact on the energy sector in many ways, including the following:

- Save energy. Individuals and companies can take many actions to save energy. For example, look for ENERGY STAR certified products, such as appliances and electronics. Some utility companies even offer federal tax credits.

- Expand access to clean technologies. Government and industry leaders can help expand access to renewable energy programs, such as wind and solar power, so that all communities benefit. This transition will help reduce the emissions contributing to climate change.

- Modernize infrastructure. Utilities and government agencies can update energy infrastructure, such as leak-prone pipelines and aging power lines. These actions increase resiliency, improve safety, and protect public health.

- Ensure energy affordability. Policymakers, industry leaders, and communities can take steps to improve energy affordability and ensure all people have a voice in energy planning. They can also better ensure that the benefits from energy investment reach typically underserved communities.

- Make infrastructure local. Utilities, urban planners, and government agencies can use microgrids. These systems and other decentralized energy infrastructure help make electricity supplies more resilient to extreme weather.

See additional actions you can take, as well as steps that companies can take, on EPA’s What You Can Do About Climate Change page.

Related Resources

- Fifth National Climate Assessment, Chapter 5: “Energy Supply, Delivery, and Demand.”

- U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. Promotes reducing carbon in the energy sector and energy-adjacent sectors such as agriculture and transportation.

- National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Supports energy efficiency and sustainability efforts and provides information on how to optimize energy systems.

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. Provides impartial statistics and analysis of energy information and increases public understanding of how energy systems interact with the economy and the environment.

- ENERGY STAR. Provides information to individuals and businesses about energy-efficient products and services.

- Energy and the Environment. Provides information and EPA resources on clean energy programs and energy efficiency. You can also measure the impact of your energy use and learn how to reduce it.

Endnotes

1 Zamuda, C., D.E. Bilello, G. Conzelmann, E. Mecray, A. Satsangi, V. Tidwell, and B.J. Walker (2018). Energy Supply, Delivery, and Demand. In Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II [Reidmiller, D.R., C.W. Avery, D.R. Easterling, K.E. Kunkel, K.L.M. Lewis, T.K. Maycock, and B.C. Stewart (eds.)]. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, USA, pp. 174–201. doi: 10.7930/NCA4.2018.CH4. p. 178

2 Zamuda, C., et al. (2018). Ch. 4: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 186.

3 DOE. (2015). Map: How climate change threatens America’s energy infrastructure in every region. Retrieved 5/11/2022.

4 Zamuda, C.D., D.E. Bilello, J. Carmack, X.J. Davis, R.A. Efroymson, K.M. Goff, T. Hong, A. Karimjee, D.H. Loughlin, S. Upchurch, and N. Voisin, 2023: Ch. 5. Energy supply, delivery, and demand. In: Fifth National Climate Assessment. Crimmins, A.R., C.W. Avery, D.R. Easterling, K.E. Kunkel, B.C. Stewart, and T.K. Maycock, Eds. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, USA. https://doi.org/10.7930/NCA5.2023.CH5, p. 5-5

5 Zamuda, C., et al. (2018). Ch. 4: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 178.

6 Zamuda, C., et al. (2023). Ch. 5: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, 5-7.

7 Zamuda, C., et al. (2018). Ch. 4: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 182.

8 Zamuda, C., et al. (2018). Ch. 4: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 182.

9 Zamuda, C., et al. (2023). Ch. 5: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 5-6.

10 Zamuda, C., et al. (2023). Ch. 5: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 5-7.

11 Zamuda, C., et al. (2023). Ch. 5: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 5-7.

12 Zamuda, C., et al. (2023). Ch. 5: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 5-7.

13 Zamuda, C., et al. (2023). Ch. 5: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 5-7.

14 Zamuda, C., et al. (2023). Ch. 5: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 5-7.

15 Zamuda, C., et al. (2023). Ch. 5: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 5-7.

16 Zamuda, C., et al. (2023). Ch. 5: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 5-12.

17 Zamuda, C., et al. (2018). Ch. 4: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 177.

18 Zamuda, C., et al. (2023). Ch. 5: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 5-7.

19 Marvel, K. et al. (2023). Ch. 2: Climate Trends. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 2-12.

20 Zamuda, C., et al. (2023). Ch. 5: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 5-8.

21 Zamuda, C., et al. (2018). Ch. 4: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 181.

22 Zamuda, C., et al. (2023). Ch. 5: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 5-8.

23 Zamuda, C., et al. (2018). Ch. 4: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 181.

24 Zamuda, C., et al. (2018). Ch. 4: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 181.

25 Nolte, C., et al. (2018). Ch. 13: Air quality. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 514.

26 Zamuda, C., et al. (2023). Ch. 5: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 5-4.

27 U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). (2021). U.S. energy facts explained. Retrieved 1/14/2025.

28 U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). (2024). United States energy & employment report 2024. Department of Energy Office of Policy, Office of Energy Jobs, p. vi.

29 U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). (2024). U.S. energy facts explained. Retrieved 8/20/2024.

30 Zamuda, C., et al. (2018). Ch. 4: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 185.

31 Zamuda, C., et al. (2018). Ch. 4: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 185.

32 Zamuda, C., et al. (2023). Ch. 5: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 5-4.

33 Zamuda, C., et al. (2023). Ch. 5: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 5-6.

34 EPA. (2022). Power plants and neighboring communities. Retrieved 3/2/2022.

35 West, J.J., et al. (2023). Ch. 14: Air Quality. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 14-23.

36 Zamuda, C., et al. (2023). Ch. 5: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 5-11.

37 Zamuda, C., et al. (2023). Ch. 5: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 5-11.

38 Kerby, J., et al. (2024) A targeted approach to energy burden reduction measures: Comparing the effects of energy storage, rooftop solar, weatherization, and energy efficiency upgrades. Energy Policy 184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2023.113867

39 EIA. (2015). One in three U.S. households faced challenges in paying energy bills in 2015. Retrieved 3/2/2022.

40 National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). (2021). NREL draws on experience to expand equitable energy access to state, local, and tribal communities. Retrieved 5/11/2022.

41 California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. (2022). CAL FIRE investigators determine cause of the Dixie Fire. Retrieved 5/11/2022.

42 Zamuda, C., et al. (2023). Ch. 5: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 5-7.

43 DOE. (2021). Nuclear 101: How does a nuclear reactor work? Retrieved 5/11/2022.

44 DOE. (2021). Nuclear 101: How does a nuclear reactor work? Retrieved 5/11/2022.

45 DOE. (2013). Climate change: Effects on our energy. Retrieved 5/11/2022.

46 Zamuda, C., et al. (2023). Ch. 5: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 5-6.

47 Zamuda, C., et al. (2023). Ch. 5: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 5-5.

48 Zamuda, C., et al. (2023). Ch. 5: Energy supply, delivery, and demand. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 5-7.