Causes of Climate Change

Natural processes are always influencing the earth’s climate and can explain climate changes prior to the Industrial Revolution in the 1700s. However, recent climate changes cannot be explained by natural causes alone.

Changes in the Earth’s Orbit and Rotation

Changes in the earth’s orbit and its axis of rotation have had a big impact on climate in the past. For example, the amount of summer sunshine on the Northern Hemisphere, which is affected by changes in the planet’s orbit, appears to be the primary cause of past cycles of ice ages, in which the earth has experienced long periods of cold temperatures (ice ages), as well as shorter interglacial periods (periods between ice ages) of relatively warmer temperatures.1 At the coldest part of the last glacial period (or ice age), the average global temperature was about 11°F colder than it is today. At the peak of the last interglacial period, however, the average global temperature was at most 2°F warmer than it is today.2

Variations in Solar Activity

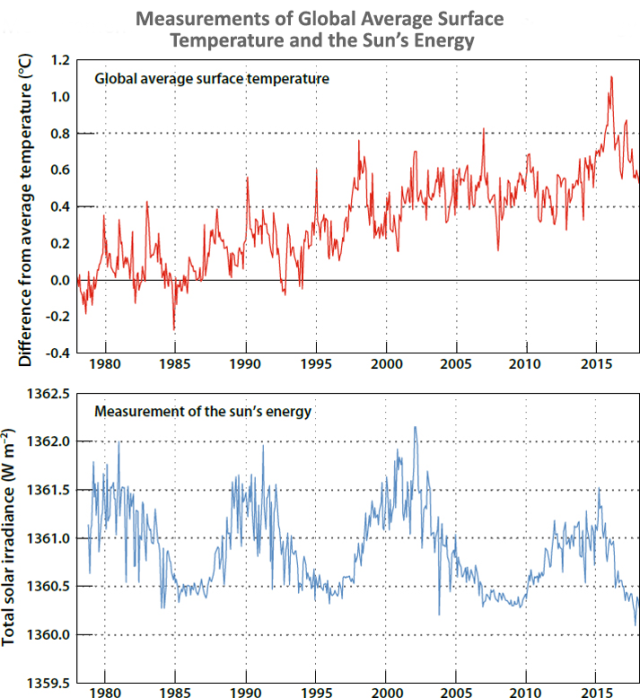

Changes in the sun’s energy output can affect the intensity of the sunlight that reaches the earth’s surface. While these changes can influence the earth’s climate, solar variations have played little role in the climate changes observed in recent decades.3 Satellites have been measuring the amount of energy the earth receives from the sun since 1978. These measurements show no net increase in the sun’s output, even as global surface temperatures have risen.4

Changes in the Earth’s Reflectivity

The amount of sunlight that is absorbed or reflected by the planet depends on the earth’s surface and atmosphere. Dark objects and surfaces, like the ocean, forests, and soil, tend to absorb more sunlight. Light-colored objects and surfaces, like snow and clouds, tend to reflect sunlight. About 70 percent of the sunlight that reaches the earth is absorbed.5 Natural changes in the earth’s surface, like the melting of sea ice, have contributed to climate change in the past, often acting as feedbacks to other processes.

Volcanic Activity

Volcanoes have played a noticeable role in climate, and volcanic eruptions released large quantities of carbon dioxide in the distant past. Some explosive volcano eruptions can throw particles (e.g., SO2) into the upper atmosphere, where they can reflect enough sunlight back to space to cool the surface of the planet for several years.6 These particles are an example of cooling aerosols.

Volcanic particles from a single eruption do not produce long-term climate change because they remain in the atmosphere for a much shorter time than greenhouse gases. In addition, human activities emit more than 100 times as much carbon dioxide as volcanoes each year.7

Changes in Naturally Occurring Carbon Dioxide Concentrations

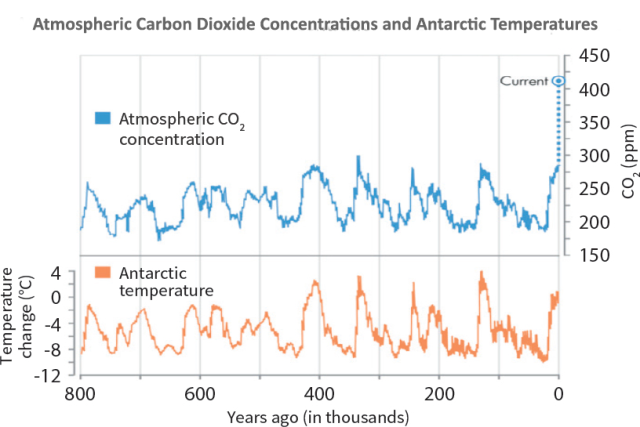

Over the last several hundred thousand years, carbon dioxide levels varied in tandem with the glacial cycles. During warm interglacial periods, carbon dioxide levels were higher. During cool glacial periods, carbon dioxide levels were lower.8 The heating or cooling of the earth’s surface and oceans can cause changes in the natural sources and sinks of these gases, and thus change greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere.9 These changing concentrations have acted as a positive climate feedback, amplifying the temperature changes caused by long-term shifts in the earth’s orbit.10

1 National Academy of Sciences. (2020). Climate change: Evidence and causes: Update 2020. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC, p. 9. doi: 10.17226/25733

2 Fahey, D.W., S.J. Doherty, K.A. Hibbard, A. Romanou & P.C. Taylor. (2017). Our globally changing climate. In: Climate science special report: Fourth national climate assessment, volume I [Wuebbles, D.J., D.W. Fahey, K.A. Hibbard, D.J. Dokken, B.C. Stewart & T.K. Maycock (eds.)]. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 53.

3Leung, L.R. et al. (2023). Ch. 3: Earth Systems Processes. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 3-5.

4 National Academy of Sciences. (2020). Climate change: Evidence and causes: Update 2020. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC, p. 7. doi: 10.17226/25733

5 Fahey, D.W., S.J. Doherty, K.A. Hibbard, A. Romanou, & P.C. Taylor. (2017). Physical drivers of climate change. In: Climate science special report: Fourth national climate assessment, volume I [Wuebbles, D.J., D.W. Fahey, K.A. Hibbard, D.J. Dokken, B.C. Stewart & T.K. Maycock (eds.)]. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 2.

6 Fahey, D.W., S.J. Doherty, K.A. Hibbard, A. Romanou, & P.C. Taylor. (2017). Physical drivers of climate change. In: Climate science special report: Fourth national climate assessment, volume I [Wuebbles, D.J., D.W. Fahey, K.A. Hibbard, D.J. Dokken, B.C. Stewart & T.K. Maycock (eds.)]. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 79.

7 Fahey, D.W., S.J. Doherty, K.A. Hibbard, A. Romanou & P.C. Taylor. (2017). Physical drivers of climate change. In: Climate science special report: Fourth national climate assessment, volume I [Wuebbles, D.J., D.W. Fahey, K.A. Hibbard, D.J. Dokken, B.C. Stewart & T.K. Maycock (eds.)]. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 79.

8 National Academy of Sciences. (2020). Climate change: Evidence and causes: Update 2020. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC, pp. 9–10. doi: 10.17226/25733

9 IPCC. (2013). Climate change 2013: The physical science basis. Working Group I contribution to the fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Stocker, T.F., D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S.K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex & P.M. Midgley (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, p. 399.

10 National Academy of Sciences. (2020). Climate change: Evidence and causes: Update 2020. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC, pp. 9–10. doi: 10.17226/25733