Climate Change Indicators: Snow and Ice

The Earth’s surface contains many forms of snow and ice, including sea, lake, and river ice; snow cover; glaciers, ice caps, and ice sheets; and frozen ground. Climate change can dramatically alter the Earth’s snow- and ice-covered areas because snow and ice can easily change between solid and liquid states in response to relatively minor changes in temperature. This chapter focuses on trends in snow, glaciers, and the freezing and thawing of oceans and lakes.

Why does it matter?

Reduced snowfall and less snow cover on the ground could diminish the beneficial insulating effects of snow for vegetation and wildlife, while also affecting water supplies, transportation, cultural practices, travel, and recreation for millions of people. For communities in Arctic regions, reduced sea ice could increase coastal erosion and exposure to storms, threatening homes and property, while thawing ground could damage roads and buildings and accelerate erosion. Conversely, reduced snow and ice could present commercial opportunities for others, including ice-free shipping lanes and increased access to natural resources.

Such changing climate conditions can have worldwide implications because snow and ice influence air temperatures, sea level, ocean currents, and storm patterns. For example, melting ice sheets on Greenland and Antarctica add fresh water to the ocean, increasing sea level and possibly changing ocean circulation that is driven by differences in temperature and salinity. Because of their light color, snow and ice also reflect more sunlight than open water or bare ground, so a reduction in snow cover and ice causes the Earth’s surface to absorb more energy from the sun and become warmer.

Summary of Key Points

- Arctic Sea Ice. Part of the Arctic Ocean is covered by ice year-round. The area covered by ice is typically smallest in September, after the summer melting season. The annual minimum extent of Arctic sea ice has decreased over time, and in September 2024 it was the sixth smallest ever recorded. The length of the melt season for Arctic ice has grown, and the ice has also become thinner, which makes it more vulnerable to further melting.

- Antarctic Sea Ice. Antarctic sea ice extent in September (annual maximum) and February (annual minimum) has increased slightly overall since 1979, though it has decreased in the last few years. Slight increases in Antarctic sea ice are outweighed by the loss of sea ice in the Arctic during the same time period.

- Ice Sheets. Since 1992, Greenland and Antarctica have both lost ice overall, with Greenland losing an average of about 175 billion metric tons of ice per year and Antarctica losing more than 90 billion per year. The total amount of ice lost from 1992 to 2020 was enough to raise sea level worldwide by an average of three-quarters of an inch or more. This accounts for about one-quarter of the total observed sea level rise during that time period.

- Glaciers. Glaciers in the United States and around the world have generally shrunk since at least the 1970s, and the rate at which glaciers are melting has accelerated over roughly the last decade. The loss of ice from glaciers has contributed to the observed rise in sea level.

- Arctic Glaciers. Rapid changes are occurring across the Arctic, where air temperatures are warming three times as fast as the global average temperature. Of the 12 Arctic glaciers with long-term measurements, 11 have steadily lost ice since the mid-20th century. The Arctic has been the dominant source of global sea-level rise since at least 1972.

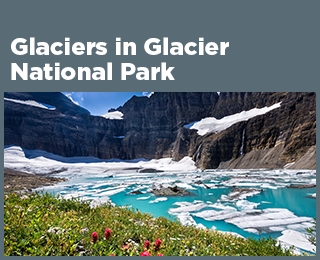

- A Closer Look: The Glaciers of Glacier National Park. Visitors from far and wide are drawn to Glacier National Park in Montana for its dramatic beauty and its glaciers. The total surface area of the 37 named glaciers in Glacier National Park decreased by about 34 percent between 1966 and 2015. Every glacier was smaller in 2015 than in 1966.

- Lake Ice. Lakes in the northern United States are freezing later and thawing earlier compared with the 1800s and early 1900s. Freeze dates have shifted later at a rate of roughly half a day to one-and-a-half days per decade. All of the lakes studied were also found to be thawing earlier in the year, with spring thaw dates growing earlier by up to 24 days since 1905.

- Great Lakes Ice Cover. Parts of the Great Lakes typically freeze every winter. Since the early 1970s, all five of the Great Lakes have experienced a long-term decrease in the maximum area that freezes each year, but the decrease is only statistically meaningful in one lake (Superior). The number of frozen days per year has also decreased for all five lakes since the early 1970s.

- Community Connection: Ice Breakup in Three Alaskan Rivers. Regions in the far north are warming more quickly than other parts of the world. Three long-running contests on the Tanana, Yukon, and Kuskokwim rivers in Alaska—where people guess the date when the river ice will break up in the spring—provide a century’s worth of community-based evidence revealing that the ice on these rivers is generally breaking up earlier in the spring than it once did.

- Snowfall. Total snowfall—the amount of snow that falls in a particular location—has decreased in most parts of the country since widespread records began in 1930. One reason for this decline is that more than 80 percent of the locations studied have seen more winter precipitation fall in the form of rain instead of snow.

- Snow Cover. Snow cover refers to the area of land that is covered by snow at any given time. Between 1972 and 2023, the average portion of North America covered by snow decreased at a rate of about 2,083 square miles per year, based on weekly measurements taken throughout the year. There has been much year-to-year variability, however. The length of time when snow covers the ground has become shorter by nearly two weeks since 1972, on average.

- Snowpack. The amount of snow on the ground (snowpack) in early spring decreased at 81 percent of measurement sites in the western United States between 1955 and 2023. Across all sites, snowpack declined by an average of 18 percent during this time period. Peak snowpack is happening earlier in the season at the majority of sites, as higher temperatures cause snow to melt sooner. Snowpack season length decreased at about 80 percent of sites analyzed, decreasing by an average of more than 15 days.

- Permafrost. About 80 percent of Alaska's land is underlain by permafrost, which refers to rock or soil that remains at or below 32°F for two or more years. Between 1978 and 2023, permafrost temperatures increased at 14 out of 15 long-term monitoring sites in Alaska. Permafrost has warmed most quickly in northern Alaska. These increases in permafrost temperatures are driven mostly by long-term air temperatures and are consistent with changes observed in other parts of the Arctic.

- Freeze-Thaw Conditions. The number of days per year with unfrozen ground has increased at an average rate of about four days per decade in both the contiguous 48 states and Alaska. Unfrozen days have generally increased across North America, with some variability by region.